Indigenous Peoples of Colombia

Achagua

OTHER NAMES:

Achagua, ajagua, xagua, "people of the river".

LOCATION:

Indigenous reservation of Umapo and El Turpial, in the municipality of Puerto López (Meta) and some families in La Hermosa (Casanare).

POPULATION:

Its population is estimated at 796 individuals (DANE 2005)

LANGUAGE:

Achagua. It belongs to the Arawak linguistic family. The use of their language takes precedence over Spanish, in addition to their continued relationship with the piapoco people, neither they also speak this language. This language was classified by the ethno-linguistic diversity protection program of the Ministry of Culture among the 19 languages that are in serious danger of extinction.

CULTURE:

Since the 18th century they have been strongly affected by evangelical missionary activity and by the expansion of colonization. Despite the process of cultural reworking and appropriation of new elements, they retain their rituals where psychotropic plants are used, essential for their ceremonies.

In Achagua groups, a type of family organization based on the father-in-law's authority prevails. The production and consumption unit and the residential unit are generally made up of an adult couple, young sons and daughters and married daughters, with their respective families. With the growth of the group, the sons-in-law tend to build separate houses.

ECONOMY:

Its main activity is agriculture. They especially cultivate bitter yucca (aliri), from which they extract the starch to make "casabe" (beri, tortilla) and "fariña" (toasted flour). They also produce corn (kana). During the summer, fishing and smaller scale hunting are important. Craftsmanship is another outstanding activity.

Sources:

-Romero, María Victoria. “Achagua“, en: Comunidades Indígenas de Colombia, Ican, Santa Fe de Bogotá, 1994.

-Romero, María Victoria. “Achagua“, en: Geografía Humana de Colombia, Región de la Orinoquia, Tomo III, Vol., 1, Instituto Colombiano de Cultura Hispánica, Santa Fe de Bogotá,1993.

-Los Pueblos Indígenas de Colombia en el umbral del Nuevo milenio – DNP –Departamento Nacional de Planeación

Recovered from: TodaColombiaPuebloACHAGUA

-República de Colombia. Ministerio del Interior. Pueblos Indígenas. Etnias de Colombia – Achagua

-Lenguas Nativas y Criollas de Colombia. Pueblo ACHAGUA.

Ambaló

LOCATION:

The Indigenous community of Ámbalo, is located in the vicinity of the Crestegallo, Puzna and Gallinazo hills whose heights exceed 3,800 m. of altitude.

POPULATION:

Taking the existing census data of the ancestral territory of the Ambalo people - socio-economic study carried out in 2007 - the Ambaló Reserve consists of 825 families, or 2749 people, 1372 men 49.70%, 1377 women 50.30 %, between paeces, abalo and guambianos people; seated in nine paths. In the ambalo territory, people living in Guambía, Totoró and from other areas of the country live in the so-called “peasant areas”.

LANGUAGE:

Namtrik

It follows that of the entire population 2749 people, 401 people speak Spanish and the native language, the rest - 2348 people - speak only the Spanish language. Undoubtedly, this worries the council, hence the Education Committee has prepared the Community Educational Project aimed at strengthening the Life Plan and the Organization for the recovery of the Territory, Language and Culture.

It is clear that the speaking population of the Namtrik is dispersed in several adjacent areas, hence an approach to the social situation of this language requires differentiated approaches.

CULTURE:

The elders tell that the town of Ámbalo originates from the union of Thunder and the Brava lagoon, major spirits that, when united, fertilize and give rise to a cacique; who goes down the Agoyan river, accompanied by the avalanche. This boy was picked up and raised until he became a man.

And so the town of Ámbalo was born. The traditional authority of the Ambaló people, throughout its existence and its historical presence, has reaffirmed its thinking, identity and culture, at the same time it has built roads, mandates and policies of resistance, autonomy and territorial control, which has been fundamental for that the 33 years of reconstitution of the authority can be commemorated together, who was disappeared by the landowners for more than four decades, during which time we have been reaffirming our existence from the territory and the living harmony deposited in our elders and mayras .

ECONOMY:

The economic activity of its people is mainly based on cattle industry and agriculture.

Sources:

-Blog "Origen Ambaló"

-Portal del pueblo Ambaló - Pueblo Ambaló hacia la consolidación.

-Reglamento Interno Ambaló SILVIA

-Territorio Ancestral Ambaló. Consejo regional Indígena del Cauca.

-Censo 2005

-Mary Luz Flórez Flórez Edison Monroy Machado - El Proyecto Educativo Comunitario -PEC- del Pueblo Ancestral Ambaló; una experiencia política y pedagógica de resistencia y pervivencia cultural. Universidad del Valle. 2015

Amorúa

OTHER NAMES:

Wipiwe, Siripu, Mariposa (Butterfly)

GEOGRAPHICAL LOCATION:

They are located in the municipality of Paz de Ariporo, Casanare, in the town of El Merey-La Guagilla. There is also a population settlement known locally as Amorúa in the town of La Esmeralda on the Aguaclara stream, a tributary of the Casanare River. There are another, of about fifteen houses, in a point near the El Porvenir herd, approximately three hours of navigation on the Meta River, who work as laborers on the farms and funds and plant cotton by contract. Other settlements are in the La Arenosa, Lithuania, Tierra Macha and Los Mochuelos reserve. The Amorúa coexist with Guahibo-Sikuani in the current Guáripa-La Hormiga reserve, in Vichada. Apparently there is more than twice the population of Amorúa than exists in El Porvenir

POPULATION:

The estimated population is 178 people, spread over a perimeter of 94,670 hectares, which are part of the Caño Mochuelo shelter.

LANGUAGE:

The group known as Amorúa or Hamorúa belongs to the Guahíbo language family. Guahibo Sikuani.

CULTURE:

Its representation system has in the figure of the Shaman the main character of the ritual and spiritual life of the ethnic group. From that perspective, the Yopo is the main psychotropic plant, fundamental in the performance of any ceremony or ritual, although it is also used in social activities. The Yopo consumption, during ceremonies, is accompanied by the consumption of tobacco and other hallucinogenic plants.

Among the most important rituals that undoubtedly mark the life cycle of the ethnic group are:

- The "fish prayer", initiation and christening ceremony, which is widely distributed among the groups in the region. Its general sense is to prepare the young woman for adult life.

The “Itomo”, which is part of the cycle of ceremonies of the second interment. It is one of the main rituals, even above the ritual of the first ceremony, where the burial is simple and only the Shaman intervenes. The ritual allows the presence of the deceased to be perpetuated and becomes an important social activity.

SOCIOPOLITICAL ORGANIZATION:

In Amorúa groups, a type of family organization based on the father-in-law's authority prevails. The production and consumption unit and the residential unit are generally made up of an adult couple, young sons and daughters and married daughters, with their respective families. With the growth of the group, the sons-in-law tend to build separate houses.

They have a system of dravidic kinship, where they classify the members of the community, and in general of the ethnic group, into two fundamental categories: that of direct blood relatives such as parents, brothers and children, as well as uncles, brothers of the same sex that the parents, brother of the father and sister of the mother and whose denominations can be translated as "father" and "mother", respectively; parallel cousins, children of the father's brothers and mother's sisters, are assimilated to the brothers, and the nephews and nieces of the brothers, are associated with their own children.

In the category of allies the brothers of the mother and sisters of the father are considered, who are both in-laws and mother-in-law, since they are the parents of the crossed cousins or virtual husbands and wives. In the lower generation, the children of the sister for a masculine ego, and the children of the brother for a feminine ego are considered as sons-in-law and daughters-in-law who are already effectively marrying the children of ego.

ECONOMY:

Cassava as the main crop, characterizes the horticulture of Amorúa groups. Bitter cassava varieties are planted intercalated up to a dozen per chagra, to achieve greater and longer production in the field. Bananas are planted in lowland areas and in humid areas. Pineapple, beans, sweet potatoes and yams are grown in small areas next to the Cassava crops, while fruit, such as guama, mango, papaya, citrus, condiments and medicinal plants are sown near the houses. For the elaboration of the alcoholic beverage, Yalaki, made from bitter cassava, an additional cassava crop is sown.

The preparation of new land (activity that takes place in” December), and sometimes planting, is carried out through the treat or “unuma, convened by the head of the settlement. The sowing takes place in the days before the first rains.

After about eight months of planting the cassava crops, production is continuous, and since each family has several conucos in different stages of development, family needs are widely met.

Sources:

-Arango y Sánchez. Los pueblos indígenas de Colombia 1997.

-Dane: censo 1993 -Proyección 2001-.

-Romero, María Eugenia. “Amorúa, Wiipiwe, Siripu y Mariposo“, en: Geografía Humana de Colombia, Región de la Orinoquia, Tomo, Vol.1, Instituto Colombiano de Cultura Hispánica, Santa Fe de Bogotá,1993.

-Fundación Hemera – Etnias de Colombia

-Los Pueblos Indígenas de Colombia en el umbral del Nuevo milenio – DNP – Departamento Nacional de Planeación

-Recuperado de: TodaColombiaPuebloAMORUA

-PNUD - UNICEF. Abril de 2009. Boletín Hecho del Callejón #45.

-Instituto Colombiano de cultura Hispánica. Geográfía Humana de Colombia. Región Orinoquia Tomo III Volumen I Amorúa

Andoque

OTHER NAMES:

Andoque "the people of the ax" - andoque, cha'oie, businka

GEOGRAPHICAL LOCATION:

They are located in the Araracuara region, Aduche canyon, very close to the banks of the Caquetá river, south of the Colombian Amazon. There are some settlements in the Peruvian region of the Ampi- Yacu River.

LANGUAGE:

Andoque is an American Indian language spoken by a few hundred Andoque Indians in the course of the Caquetá River in Colombia, and currently in decline in terms of number of speakers.

In 2000 it was reported that there were 610 speakers in the Anduche River area, downstream from Araracuara (Amazonas, Colombia); 50 of them were monolingual in that language. Previously, the language had also been spoken throughout Peru. 80% of speakers speak Spanish fluently.

POPULATION:

The population was quickly decimated by the effects of rubber exploitation that occurred in past decades. Of the almost 10 thousand habitants that existed, now only 597 people are registered.

CULTURE:

They traditionally occupied a wide territory that extended from the Monochoa gorge, above the Araracuara stream to the Quinche gorge, both tributaries of the Caquetá river. They were divided into relatively autonomous lineages that comprised more than 10,000 people; each lineage lived in a maloka, epicenter of the social, spatial and ceremonial life of the group.

Ethnohistorical evidence, speak of extensive networks of exchange between groups in the region that inhabited different environments. The Andoque provided stone axes, excavated in their territory within the framework of complex rituals that placed this activity in an important place within their worldview and ethnic identity. The shortage of stone in the area as well as access to these tools gave the group a privileged position for the exchange.

Although the expeditions of conquest and colony of the territory in the seventeenth century by Spaniards, Portuguese and Franciscans produced great changes in the Amazonian territory, the cycle of "the rubber industry" at the beginning of the twentieth century, was the most significant milestone in its history, generating profound transformations and adaptations in its cultural life. As a result of this activity not only the majority of the population disappeared, but also metal and merchandise instruments were introduced massively, new economic systems were adopted and different models of authority were promoted.

After ethnocide, the forced transfers of the population to the Ampi-Yacu River and the disarticulation of society, the few survivors began a complex process of ethnic reconstruction that is currently still in force. Under this framework, once the time of the Arana house and the Colombian-Peruvian conflict ended, the members of each lineage built new malokas, formed exogamous and patrilocal units with their own name and, as a demographic strategy, they integrated people from other ethnic groups. Its economic activity continued to be the extraction of rubber, incorporating the figure of the employer within its sociopolitical and cosmological organization.

Historically, the Andoque and other groups in the region have been affected by the different processes of colonization, expansion of the agricultural frontier and extraction of natural resources, including cocoa, quina and rubber. Likewise, the recent insertion of the region into the market economy system has shaped the cultural dynamics of the ethnic group and its territory.

ITS CULTURE:

For the majority of towns that inhabit the Amazon region, the use of sacred plants constitutes a fundamental element in their cultural and social life. The Yuruparí is the most transcendental ritual because it recalls the origins and revives the essential elements of its worldview.

They traditionally occupied a large territory that extended from the Monochoa stream, above the Araracuara stream to the Quinche stream, both tributaries of the Caquetá river. They were divided into relatively autonomous lineages that comprised more than 10,000 people; each lineage lived in a maloka, epicenter of the social, spatial and ceremonial life of the group.

Ethnohistorical evidence, speak of extensive networks of exchange between groups in the region that inhabited different environments. The Andoque provided stone axes, excavated in their territory within the framework of complex rituals that placed this activity in an important place within their worldview and ethnic identity. The shortage of stone in the area as well as access to these tools gave the group a privileged position for the exchange.

ECONOMY AND HOUSING:

The andoke base their production system on activities such as agriculture, fishing, hunting and gathering, as well as logging on a smaller scale. The main crops are cassava, sweet cassava, banana and pineapple. In recent years colonization has contributed to Andoque introduce semi-permanent crops such as bananas, cane and corn.

In his shelter there are currently three malokas where people of the highest rank live. Around them, the homes of large families belonging to the respective patrilineal clans are grouped. Gavilán, Venado, Sol, Hormiga Arriera and Cucarrón are the consolidated clans today. Within its worldview, maloka continues to be the confluence space of the social, economic, cultural and ritual structures of the community. In the social sphere, the authority falls on the "maloquero" who is in charge of the direction of the ritual life.

Sources:

-Arango y Sánchez. Los pueblos indígenas de Colombia 1997.

-Dane: Censo1993 -Proyección 2001-.

-De la Hoz, Nelsa. Caracterización de los patrones de cacería en la comunidad de Aduche y el asentamiento de Pto. Santander, Tesis de grado, Departamento de Biología, Universidad Javeriana, Santa Fe de Bogotá,1997.

-Espinoza, Mónica. Convivencia y poder político entre los andoques, EUN, Santa Fe Bogotá,1995.

Recuperado en: TodaColombiaPuebloAndoque

-Aschmann, Richard P. (1993). Proto Witotoan. Publications in linguistics (No. 114). Arlington, TX: SIL & the University of Texas at Arlington.Campbell, Lyle. (1997).

-American Indian languages: The historical linguistics of Native America. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509427-1.

-Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (Ed.). (2005). >Ethnologue: Languages of the world (15th ed.). Dallas, TX: SIL International. ISBN 1-55671-159-X. (Online version: http://www.ethnologue.com).

-Greenberg, Joseph H. (1987). Language in the Americas. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

-Kaufman, Terrence. (1994). The native languages of South America. In C. Mosley & R. E. Asher (Eds.), Atlas of the world's languages (pp. 46-76). London: Routledge.

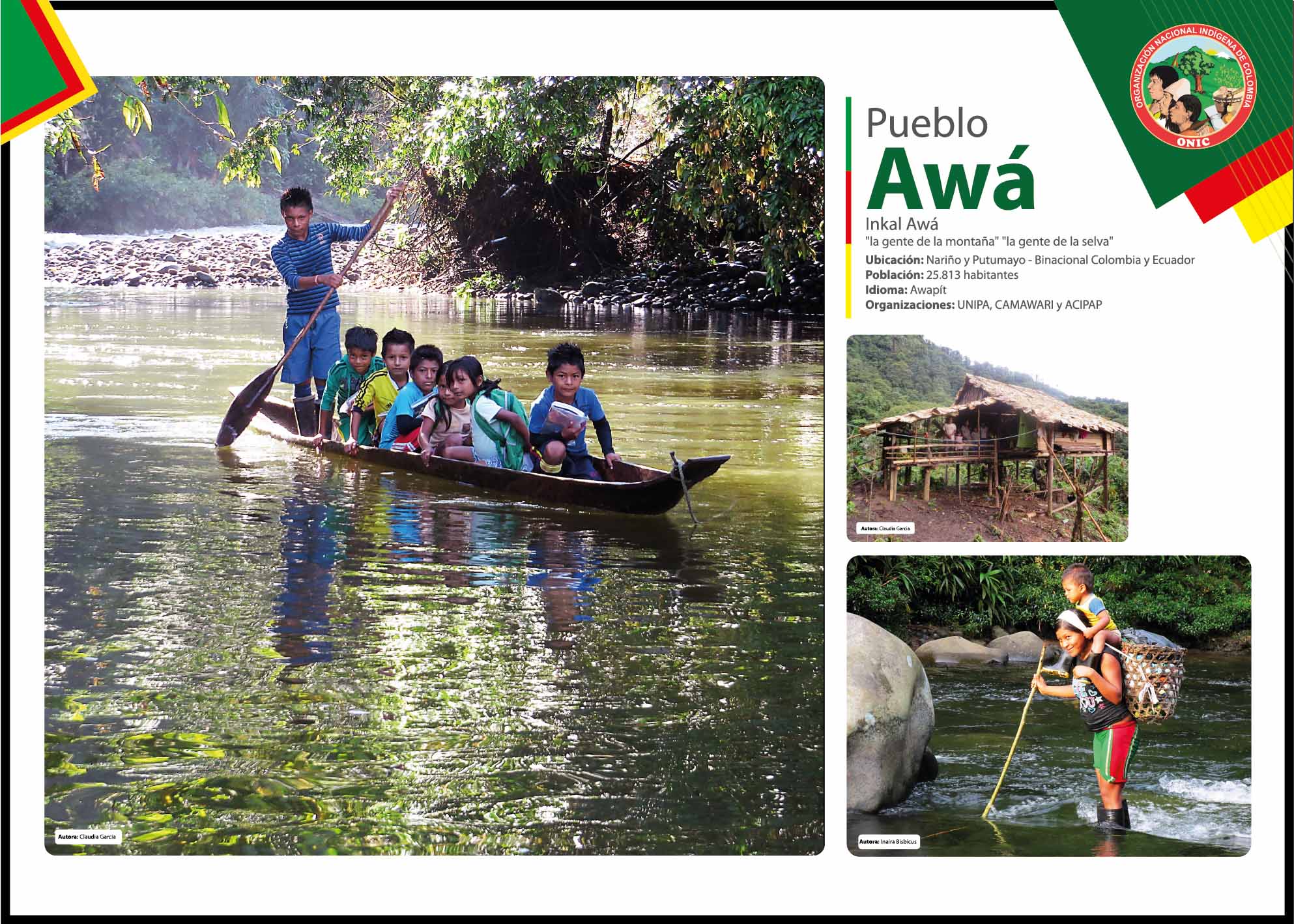

Awá

OTHER NAMES:

Awá "the people of the mountain" "the people of the jungle" - Awá, cuaiquer, kwaiker

GEOGRAPHICAL LOCATION:

The Awá have a binational presence; They are found in Colombia and Ecuador. In Colombia they are located in the southwest in the municipalities of Cumbal, Santa Cruz de Guachavez, Mallama, Ricaurte, Barbacoas, Roberto Payán, Tumaco and Ipiales, in the department of Nariño, and in the municipalities of Mocoa, Puerto Asís, Valle del Guamuez, San Miguel, La Dorada, Orito, Puerto Caicedo, Villa Garzón in the department of Putumayo.

LANGUAGE:

From the Awapit language, which belongs to the Chibcha language family. It is part of the Sindaguas Malla dialect; related to the Chá palaa (language of the Chachi Nationality) and with the Tsa'fíqui (language of the Tsa'chila Nationality).

POPULATION:

With an approximate area of 3000 square Kilometers, the ethnic group is characterized by dispersed settlements that follow the current of the rivers. Its population is estimated at 25,813 people (DANE. 2005. National Population Census)

The climatic conditions make that the highest population concentrations are located in the altitudinal part of the 500 to 1,500 meters above sea level, since the indigenous people seek the low terraces to cultivate and build their homes, while the upper part of the massif is an area reserved for hunting.

CULTURE AND HISTORY:

The origin of the ethnic group is uncertain and confusing, since archaeological studies show that the coast, both Colombian and Ecuadorian, was inhabited by the Tumaco culture. Upon the arrival of the Spaniards in 1525, the chronicles give account of semi-nomadic indigenous groups with a very low degree of development in relation to the other ethnicities found in the Andean region.

During the colony, the groups in the region, generically referred to as "Barbecues", were grouped into "Indian villages", according to the Hispanic population model. The colonizing pressure of the region increased significantly as this area became one of the main gold fields and port centers - in the case of Barbacoas - a situation that forced the indigenous people to move outside their traditional territory.

Its location in one of the communication axis between the coast and the Andean plateau, has significantly influenced the conformation of its territory, which has been affected by mining booms, civil wars, livestock colonization processes, timber and of illicit crops, in addition to large infrastructure works such as the road to the sea. From the sixties, when the arrival of settlers, miners and palm oil extractors intensified, many indigenous people had to restart the migratory processes.

The highest indigenous concentration is found in the municipality of Ricaurte, due in part to the climatic conditions that allow greater agricultural activity. These same factors have favored the colonization of these lands and other areas to the detriment of indigenous settlements, mainly in areas near the road and marketing centers, such as Talambí, Numbí, Puente Piedra, Pialapí, San Pablo, Cuayquer Viejo, Vegas and El Diviso.

About the AWÁ culture : The cultural dynamics in the Awá people are primarily promoted by the elders (men and women) in their capacity as custodians of the inherited traditional knowledge and in turn the bridges for the spiritual connection of the community. Their role is fulfilled in the form of wise men, traditional doctors and spiritual guides.

The Awa have a great influence of the peasant peoples that inhabit the region, which especially affects the new generations. Traditional aspects, such as dress, have been disappearing with the passing of time. In most settlements practices such as basketry are preserved, whose elaboration is still at hand. In the poorest and most remote regions, utensils are still made of clay and wood, but it is very common that they no longer use objects of an ancestral nature, since they have been replaced by western objects such as lighters, plastic vessels, thermos, mills, etc. Within its worldview the world is populated with supernatural beings. Magic plays an important role as does the practice of Catholic rituals.

ECONOMY AND HOUSING :

Although hunting was their traditional subsistence activity, the unfavorable conditions of their environment have forced them to develop other economic activities such as agriculture, fishing and raising domestic animals. Its agricultural system focuses on the "felling and rotting" technique. The main product is corn, which is combined with the sowing of cassava, beans, sugar cane and plantain. In lands not suitable for agriculture, edible products, medicinal plants and construction timber are collected. The extraction of gold from alluvium occupies a complementary line within its economy.

THEIR HOUSING :

Awa housing follows the construction line that characterizes the Pacific region, that is, aerial housing. Its structure consists of one bedroom, one kitchen and a very wide corridor. They are houses made of chonta and gualte palm leaf, which are crushed to form a mat. The floor is made of wood and the roof has a wide slope to evacuate the water when it rains. Domestic animals are collected in the space under the house.

Their residence pattern is characterized by the dispersion of their settlements along the rivers. They live in houses separated from each other, for several hours on the way. The settlements have a nucleus of houses belonging to people with direct ties of consanguinity, who in turn exercise management functions of the settlement.

Sources:

Arango y Sánchez. Los pueblos indígenas de Colombia 1997.

Dane: Censo1993 -Proyección 2001-.

Martínez, Edgar et. al. Comunidad Cuayquer, Diagnóstico Preliminar, Pasto, Colombia, 1984.

Perafán, Carlos C., Azcárate Luis José. Sistemas Jurídicos Cocama y Awa, Ican, Santa Fe de Bogotá,1997.

Osborn, Anne. Estudios sobre los indígenas Kwaiquer de Nariño, Colcultura, Ican e Icbf, Santa Fe de Bogotá,1991.

Fundación Hemera – Etnias de Colombia.

Los Pueblos Indígenas de Colombia en el umbral del Nuevo milenio – DNP – Departamento Nacional de Planeación.

-Recuperado de: TodaColombiaPuebloAWA

-República de Colombia: Colombia. Ministerio del Interior. Awa Kuaiker.

Artículos Relacionados:

Bará

OTHER NAMES:

"people of peace" waimaja, posanga-mira. North Barasana.

LANGUAGE:

Bará (waimaja, waimasa, waymasa, waimaha, northern barasano). It belongs to the Tucano Oriental linguistic family.

GEOGRAPHICAL LOCATION:

The Bara indigenous people are located in the northeastern part of the Amazon, exactly in the department of Vaupés, Colorado, Papuyurí, Yapú, Inambú, Macucú and Tiquié rivers.

POPULATION:

Its population is estimated at 208 people (DANE 2005) They are divided into the following clans: Waimasa, Wamutañara, Pamoa, Bara. Wañaco and Bupua - Bara.

CULTURE:

In recent years there have not been enough studies on the trajectory of this group or its current situation. However, they have been classified in ethnography as part of the so-called cultural complex of Vaupés, a characteristic that resembles other nearby groups, belonging to the Tucano Oriental linguistic family such as the Tatuyo, Desano and Wanano.

Within its worldview, each species of animals has its maloka and its owner. After death, the soul leaves for the maloka of the ancestors. The maloka is exclusively for people, for this reason those who do not consider themselves totally human, as is the case of newborns or stung by snakes, cannot enter until the Shaman, a figure of great importance in the community, Do not grant them this condition. According to ethnography, one of the most prominent ceremonies was that of the “Dabucurí” or exchange ceremony, where visitors brought meat and fish and the hosts offered cassava beer.

ORGANIZATION:

The sociopolitical structure of the Bara people responds to a complex system of hierarchical organization, divided into patrilineal lineages. However, this structure has been gradually modified, due to the pressure of the settlers in the area, which have forced them to adopt forms of organization that are totally opposed to the traditional ones. For example, in ancient times the power fell on the shaman or curaca, who not only governed the spiritual destinies of the ethnic group, but also made all kinds of decisions of transcendence. Its form of political organization is supported by the council, whose members are elected for a period of one year.

ECONOMY AND HOUSING:

The economy of this group is based on logging and burning, hunting, fishing and gathering. Its main crop is cassava followed by bananas, yams, sweet potatoes, sugar cane, dyes and medicinal plants. They also raise chickens for trade and some wild birds that use their feathers for ritual decorations. For fishing they use the hook, bows, arrows and traps. Growing hallucinogenic plants is always a male trade, while basketry and everything related to wood, and pottery is exclusive to women.

THEIR HOUSING:

By the mid-eighties, this group still lived in malokas and in nuclear villages of 12 to 60 people. It is possible that at present, like other towns in the region they have adopted the model of the town where the houses are grouped around a maloka, a school and a soccer field.

Sources:

Arango y Sánchez. Los pueblos indígenas de Colombia 1997.

Dane: Censo 2005-.

Instituto Lingüístico de Verano, 1979:1.

Telban, Blas. Grupos étnicos de Colombia, etnografía y bibliografía, tercera colección 500 años, ediciones Abya-Yala, Movimientos Laicos para América Latina, Quito, Ecuador, 1988.

Fundación Hemera - Etnias de Colombia

Los Pueblos Indígenas de Colombia en el umbral del Nuevo milenio – DNP – Departamento Nacional de Planeación

-Recuperado de: TodaColombiaPuebloBARA

-Portal de lenguas de Colombia. Awapit.

Barasano

OTHER NAMES:

Southern Barasano, eduria, yebá-masã, yepa-mahsã, yepá-matsó, hanerã (or janena), paneroa, komea, teiuana (or taiwano), banera yae, hanera oka

GEOGRAPHICAL LOCATION:

Amazon. Colombia and Brazil Their territory is included in the Eastern Part of Vaupés, they live in Caño Colorado, Pirá-Paraná River. This indigenous people is also known as southern barasana, Janera, Panera

POPULATION:

Its population is estimated at 350 individuals. They are scattered in several departments of the country. The highest population concentration of this indigenous people is found in the municipality of Mitú - Vaupés with a total of 162 indigenous people, followed by the municipality of Leticia - Amazonas with a total of 40 people. The distribution of the barsana population by gender corresponds to 177 men and 173 women. It is one of the villages in which it is distinguished by its low population density. We found barsana population in other regions of the country (Valle, Guaviare, Meta) although in a very small amount compared to the main settlements.

LANGUAGE :

Barasana-taiwano

Their language belongs to the Tucano Oriental family, characteristic that groups them in the so-called complex of the region of the Eastern Part of Vaupés, they live in Caño Colorado, Pirá-Paraná River. It is one of the 15 languages of the eastern Tucano family among them (bara, barasana - taiwano, carapana, desano, kubeo, makuna, tatuyo, tukano, tuyuka, wanano, yurutí and pisamira

CULTURE:

Traditional dress, music and instruments such as marimba, big drums, flutes and cununos (small drumbs), traditional medicine, production techniques in agriculture, fishing, hunting and animal husbandry, are part of their identity.

The elders tell that, at the beginning of humanity, the anaconda snake, climbed the river and left the different groups that today live in the Vaupés jungle. Since then, the Barasana del Pirá-Paraná have lived in the jungle, gradually discovering their secrets, without destroying the life of plant and animal species. Many rivers flow through the jungle. They are people of canoes, harpoons, traps and hooks. Among the trees in the jungle they learn to choose the one they will transform into a canoe.

The myth among the Barasana relates their daily lives with the world of heroes and beings of nature, ordering the world in an intelligible way. The symbology is highly sexualized. At parties it is danced, myths are recited and hallucinogens are taken. The "Yurupari" secret flutes stand out for their importance in festivities and ceremonies.

HOUSING :

The barasana live in multi-ethnic settlements. However, as is the case of Piedra Ñi, these are often relocated based on inter-ethnic tensions and offers from the territory. Traditionally, the maloka, rectangular, was the center of social, economic and ceremonial organization. In recent years, the pattern of nucleated dwellings around a maloka has been adopted.

ORGANIZATION:

Traditionally the main authority is the chief of the maloka, however, there are other characters that perform religious functions such as Payé, the kumu, the specialist in songs and dances and the teacher of myth recitation. They are considered allies of the makuna.

ECONOMY :

Combine itinerant agriculture with hunting, fishing, gathering and crafts. The land for sowing opens by knocking down a small section of jungle at the beginning of summer and burning before the rains begin. The main crop is the bitter yucca kî, sown by women, who also plant sweet potatoes, chonque, yams, pumpkins, sugar cane, bananas, pineapple, cashew and other fruit trees. The men sow corn, chontaduro, avocado, wamü, tobacco, coca and yajé.

Women are potters and make different kinds of clay pots and the large pan or "budare" to make casabe of cassava. Men are responsible for basketry and carpentry.

They hunt with blowgun, bow and arrow, javelin or shotgun. Among the dams are the danta, the peccary, monkeys, armadillo, chacures and different birds. They collect wild fruits, meca jia ants, grasshoppers, bee larvae and "mojojoy" (wadoa) and edible beetles. They generally fish with hook and have canoes made by themselves.

The kûmû (shaman) knows how to use yajé, coca and tobacco to interact with the spiritual world and promote the success of the economy, food and health.

The division of labor by sex and age is presented. Men's work consists of preparing the land, fishing, hunting and manufacturing crafts, while women are responsible for keeping the chagra clean, harvesting and preparing food. Horticulture is the basis of its economy with the traditional logging and burning system.

The central crop is bitter cassava and its derivatives are the source of daily food. On a smaller scale they grow corn, squash, bananas, sugar cane, activities that complement hunting, fishing and the collection of worms, ants and wild fruits. Recently they have ventured into commercial fishing.

Sources:

Arango y Sánchez. Los pueblos indígenas de Colombia 1997.

Dane: Censo1993 -Proyección 2001-.

Hernández, Jaime Alberto. Migración, asentamiento y contacto cultural en las comunidades indígenas del río Mirití- Paraná, Tesis de grado, Departamento de Antropología, Facultad de Ciencias Humanas, Universidad Nacional, Santa Fe de Bogotá,1991.

Telbán, Blas. Grupos étnicos de Colombia, etnografía y bibliografía, tercera colección 500 años, ediciones Abya-Yala, Movimientos Laicos para América Latina, Quito, Ecuador, 1988.

Fundación Hemera - Etnias de Colombia

Los Pueblos Indígenas de Colombia en el umbral del Nuevo milenio – DNP – Departamento Nacional de Planeación

-Recuperado de: TodaColombiaPuebloBarasana

-Ministerio de Cultura. República de Colombia. Lenguas Nativas de Colombia Lengua BARASANO

-Ministerio de Cultura. República de Colombia. BARASANO Los hijos de Mení y Warími.

-Atlas sociolingüístico de los pueblos indígenas en América Latina. Tomo I. 2009. UNICEF

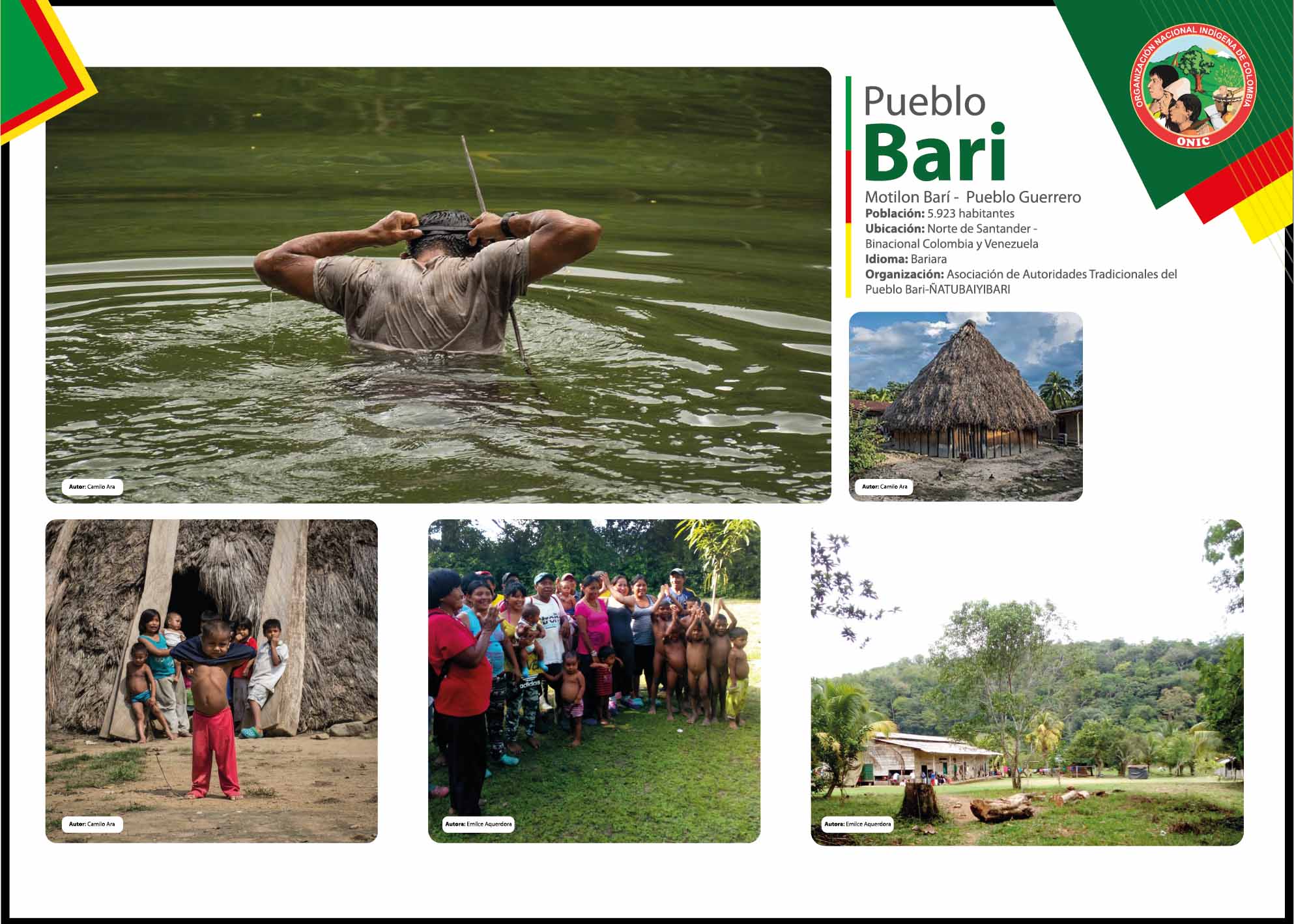

Barí

OTHER NAMES:

Motilone barí, motilón, Barís, barira, dobocubi, cunausaya

GEOGRAPHICAL LOCATION :

They live on the border with Venezuela in the serranía de los motilones, (range of mountain of the Motilones), department of Norte de Santander; the Bari are located on the pit of the Catatumbo River, a forested region - humid tropical - composed of lowlands that descend from the Santurbán knot, in the eastern mountain range. The different water currents, which run in a south - north direction and that cross the department of Norte de Santander, converge in the macro region of Lake Maracaibo.

The main geographical accident that shelters the Barí is the serranía de los motilones, between the Cerro de Mina (south) (the mina Hill), the sources of the Catatumbo River and the Sierra del Perijá (north) (Perijá Hill), under the jurisdiction of the municipalities of El Carmen, Convention and theorem. It is a region with an average temperature of 24 ° C and rainfall levels estimated at 2,500 mm, where winters occur in the months of April - May and October - November, and summers in the months of December, January and February .

POPULATION :

This indigenous people has a population of 5,923 people, of whom 4,897 are in the municipal headwaters. The municipalities with the highest concentration of this publication are Cúcuta and Tibú

LANGUAGE :

This language is called BARÍ ARA; God Sabaseba, was the one who organized the world and their lives and the most feared of the spirits is Dabiddu, owner of the night, spirit that causes evil and who, with his fatality brings disease and death to Barí. The language Bari Ara, designates rivers words that mean living beings because they move. For these reasons there is a huge pain in the Bari People, because on the occasion of oil exploitation they are hurting us and the spirit feels it.

CULTURE AND HISTORY :

From pre-Hispanic times the area was characterized by permanent intercultural contact between the groups of the surrounding regions. By the time of the conquest, they occupied an extensive territory from the Venezuelan Andes to the Serranía del Perijá. The group maintained its resistance to “pacification” for almost five centuries by developing adaptation mechanisms, such as its pattern of multiple residence that allowed the relative isolation of populations. However, the Capuchin missions managed to establish themselves in their territory since early times, allowing contact with the majority society.

From the first decade of the twentieth century, concessions were made for oil farms in the Barí territory, encouraging the opening of roads and the massive colonization of the region; before which, the reaction of the natives was violent, causing the beginning of a long war process against the oil companies that would last until the sixties. Missionary action intensified in the area and continues to the present, developing a policy of "integration and development" of the Barí and Yuko communities.

CULTURE:

They believe in a supreme being, they invoke it in diseases, when they go fishing, hunting and harvesting. But this religion has no constituted "authorities" that can transmit since they deform from generation to generation. The supreme being or "Saymaydódjira" is the God from the beginning before the existence of the motilón and therefore the Creator. When it is considered that a child has already acquired the necessary skills to survive autonomously, then the father gathers a few close relatives in an isolated place, and there in that meeting they confer the adult status to the boy by delivering the guayuco

ECONOMY:

They practice logging and burning horticulture, fishing and hunting. Its traditional cultivation is sweet cassava, although other species such as bananas, corn, cane and cocoa have been adopted. It is common to raise pigs and poultry for sale in the market. They complement these activities with the day laborer. Some groups interleave commercial and traditional subsistence practices.

HOUSING :

Its traditional residence pattern is characterized by the possession of three huts arranged cyclically, periodically inhabited by each local group. The bohío or communal house -rectangular or oval- is the center of the Barí culture and activity, surrounded by a main and secondary conuco.

Currently, there is a tendency - driven by missionaries - towards the adoption of a fixed pattern of residence through the construction of hamlets, partly as a defense strategy for the territory they own. However, seasonal huts are still maintained in some places, despite the introduction of livestock and cash crops. Two of its main settlements are called Hitayosara and Ikiakarora.

SOCIOPOLITIC ORGANIZATION :

Socially organized in local communities whose kinship relations are defined according to the group of residence. These communities are divided into consanguineous brothers and political brothers. The minimum unit of work is the “home” consisting of a group of “brothers” men and their related wives. Its political system is egalitarian and is based on the recognition of various roles transferred from generation to generation.

Sources:

Arango y Sánchez. Los pueblos indígenas de Colombia 1997.

Dane: Censo1993-Proyección 2001-.

Jaramillo Gómez, Orlando. “Los Bari“, en: Geografía Humana de Colombia, Nordeste Indígena, Tomo II, Instituto Colombiano de Cultura Hispánica, Santa Fe de Bogotá,1993.

Fundación Hemera - Etnias de Colombia

Los Pueblos Indígenas de Colombia en el umbral del Nuevo milenio – DNP – Departamento Nacional de Planeación

Recuperado en: TodaColombiaPuebloBarí

-Ministeriodel Interior. República de Colombia - Caracterización Pueblo Motilón Barí

-Ministerio de Cultura. República de Colombia - 200 años CULTURA ES INDEPENDENCIA - Bari, hijos de sabaceba y gente de los ojos limpios

-Página web. ASOCBARÍ. Pueblo Indígena Barí. Axbibumbi Shidemánumay Aibaynobi Yaphidódari.